The third instalment of Bushcraft and the Law, this article is all about the legal spring and live catch traps that can be used in the UK countryside.

Many of us who practice bushcraft are interested by primitive trapping, but can this mean we fall foul of the law?

To my mind one of the most telling tests of someone’s bushraft ability is whether they can consistently provide food for themselves in the wilderness. A significant part of that ability is going to be knowledge of effective methods of taking birds, mammals and fish as food. This is where, in practicing bushcraft as a hobby there can be some difficulty. Although our primitive ancestors would not have been restricted in their hunting methods by law and legislation WE ARE.

Traps have been used for thousands of years to procure food, they are doubly effective when compared to active hunting in that they can be set and left to ‘hunt’ all on their own without your direct supervision or intervention, leaving you to get on with other important things. You can set more than one at a time, maybe even hundreds depending on your needs. In modern terms, at least in the UK, they are used primarily as a means of controlling pests and predators rather than a means of procuring food. Agriculture is the main reason for this as we no longer need to subsist by means of a hunter gatherer lifestyle, but also trapping, especially snares and other live catch traps are stressful for the quarry and catching them by these methods means that due to adrenaline and other chemicals released into the body of a stressed animal the quality of the meat is poorer in trapped animals than ones killed instantly, for example by a high velocity rifle bullet. Despite these limitations traps are a truly effective and efficient method of catching quarry.

Primitive methods of acquiring food are probably of most interest to those of us who practice bushcraft as we want the challenge of being able to use the minimum of man-made material, and depending on how far we want to test our skills perhaps even resorting to primitive tools to construct the traps or weapons that could be used in gathering food. But please be aware that practicing making primitive hunting and trapping implements is fine but almost all primitive methods of taking mammals and birds are now legislated against on grounds of animal welfare. This means no bows, spears or bolas, for killing anything. No figure four deadfalls or pit traps, build them yes but actually using them to catch or kill something is ILLEGAL!

Most of you have probably heard of the four basic methods of trapping; mangle, tangle, dangle, strangle, however in modern trapping we have to avoid any of these terms, legal traps now fall into three basic categories.

Spring Traps

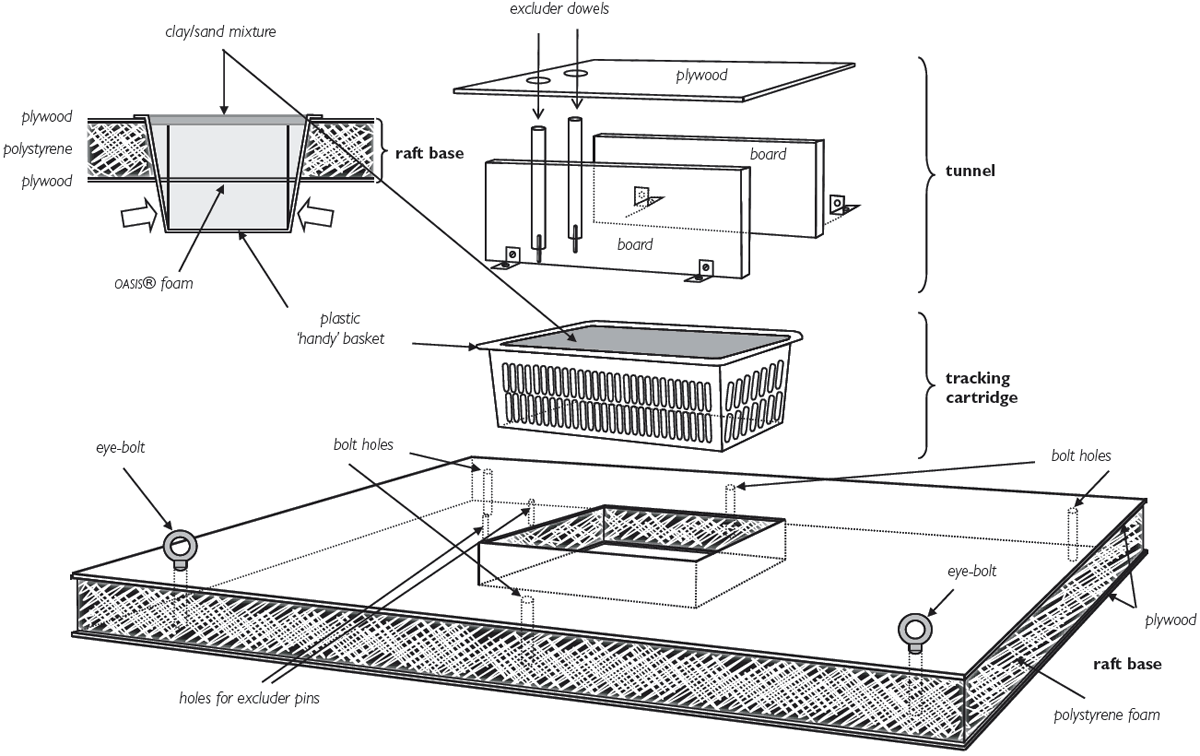

Spring traps are the closest we get to a ‘mangle’ style trap but they are designed to kill instantly by breaking an animal’s spinal column. To be used legally a spring trap must be approved by the ‘Spring Trap Approval Order’ England Wales and Northern Ireland all have their own version of this legislation and these were updated in 2012, in Scotland the last update of the spring trap approval order was 2011. This piece of legislation designates which traps have been approved for use and also designates which species can be targeted with which trap and how non target species should be restricted from access to the trap.

| Fenn Mk IV |

For example the traps such as the fen mark IV or the Solway mk 4 are often used for trapping small vermin such as rats, weasels, stoats and grey squirrels the trap must be enclosed in a natural or artificial tunnel which restricts access to non-target species. As well as a tunnel I always place stout sticks or use wire mesh across the front of the tunnel to stop birds, cats and hedgehogs getting caught by mistake (as pictured below)

These traps are all best set along existing linear features such as hedgerows or using naturally occurring cover such as tree roots like in the picture below.

It is also best to set the traps into a shallow scrape in the ground so they are not as easily visible if you look through the tunnel from ground level, this way they will not put off an animal from entering the trap.

These traps should all be weathered before use by burying them or leaving them outside for a while so the smell from any grease or lubricant used in their manufacture is diminished and they lose their shiny appearance. These traps are generally not baited although some like the magnum trap (below) can be, the attraction is the cover provided by the tunnel that the trap is set in and when placed in the appropriate location these traps can be very effective. They can be made more attractive by the removal of grass and plant matter from their entrances leaving some bare soil which seems to attract quarry species to enter the tunnels. These types of trap must, by law, be checked at least once every 24 hours.

Live Catch Traps

This is one type of trap where you may be able to use some primitive triggers, live catch traps do what they say on the tin, they catch and hold an animal until it can be identified and either released or dispatched humanely. Common traps which fall into this category are Larsen traps for catching corvids such as crows and magpies. Cage traps for catching foxes, badgers, otters, mink, squirrels etc.. and large ladder traps for catching multiple birds at once. It’s also worth mentioning that when using any trap which requires a decoy bird (such as a Larsen trap) you must provide a food, clean water, a perch and shelter for the captive bird.

Pheasants and partridges are also caught by game keepers to use for breeding purposes, each year before the end of the shooting season on the 1st of February live catch traps made from steel mesh or from partridge pens are used to catch birds that will later in the year produce the eggs for the next crop of birds. Traditionally a much more primitive method was used and keepers would have used this kind of trap made from willow or hazel sticks and baited with corn or wheat to catch their pheasants and partridge breeding stock. This is where the primitive trapping comes in and these traps would often have been triggered by a split stick trigger and a trip wire. It is still acceptable to use these traps, although obviously with the landowners permission.

I haven’t tried to name every piece of legislation that refers to trapping here, or talk about seasons for catching and/or killing certain species or legislation regarding access to land; all that legislation is available via www.legislation.gov.uk.

Key things to become familiar with include;

- The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981

- The Spring Trap Approval Order (England, Wales and Northern Ireland 2012) (Scotland (2011)

- The Snare Orders (Scotland) 2010 and 1012

- The Game Act 1831

- The Night Poaching Act 1828

- The Crow Act 2000

- The Hunting Act 2004

These are just some of the legal methods of trapping and some of the legislation which governs how we can take wild animals, make sure you are familiar with what you can and can’t do in the name of bushcraft so you don’t get yourselves in trouble.

In the next instalment I'll be looking at snares.