They pop up in large clumps and are smooth, grey and dome shaped, generally smaller than their shaggy (Coprinus comatus) cousins they do however share that same trait, as do all the ink caps, of decaying into an inky mess after a day or two. In fact it is from this trait that the species derives it's name atramentaria from the Latin 'atramentum' for 'ink'. Originally classified as belonging to the genus Agaricus, as was the shaggy ink cap, they were later re-classified as belonging to the genus Coprinopsis. Ink cap is as much a description as a name as the unique trait of these species is that to spread their spored their gills secrete a fluid filled with spores (this spore print can be seen in the picture on the right) and eventually the entire fruiting body turns to an inky slime and disintegrates. For this reason although common and shaggy ink caps are both edible and delicious they must be eaten very fresh as within a few hours of picking this decay will begin.

They pop up in large clumps and are smooth, grey and dome shaped, generally smaller than their shaggy (Coprinus comatus) cousins they do however share that same trait, as do all the ink caps, of decaying into an inky mess after a day or two. In fact it is from this trait that the species derives it's name atramentaria from the Latin 'atramentum' for 'ink'. Originally classified as belonging to the genus Agaricus, as was the shaggy ink cap, they were later re-classified as belonging to the genus Coprinopsis. Ink cap is as much a description as a name as the unique trait of these species is that to spread their spored their gills secrete a fluid filled with spores (this spore print can be seen in the picture on the right) and eventually the entire fruiting body turns to an inky slime and disintegrates. For this reason although common and shaggy ink caps are both edible and delicious they must be eaten very fresh as within a few hours of picking this decay will begin.  |

| Decaying shaggy ink caps. |

There are many ink cap species, over 120 in fact and while the topic of this post will relate specifically to the common ink cap and it's edibility there is an ink cap species, native to the UK although not particularly common, that is poisonous, the magpie ink cap (Coprinus picacea).

On to the main event though; the common ink cap and it's fickle edibility, sometimes it's edible, sometimes it isn't but why? To explain why it is sometimes inedible we need to refer to one of it's colloquial names; tipplers bane. This name refers to the fact that this particular mushroom is poisonous when combined with alcohol.

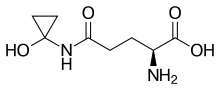

What it actually creates is an extreme sensitivity to alcohol with similar consequences to drugs specifically used to combat alcohol addiction such as disulfiram which inhibits the function of the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. The compound present in common ink caps which causes this is something called coprine.

|

| Coprine |

Coprine doesn't stop the production of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase but rather blocks it's action and it's this enzyme that is responsible for many of the effects of a hangover. What you get if you have eaten common ink caps and consume enough alcohol to raise your blood alcohol concentration to about 5mg/dL you will feel the effects of this poisoning in the form of a reddening face, nausea, vomiting, tingling in the limbs and eventually in extreme cases, the effects of the poison grow worse the more alcohol you consume, cardiac arrhythmia.

So there you have it, that's what make the common ink cap a 'tipplers bane'.

As you will have read plenty of scientific names for fungi in this post I've decided to do another Bushscience post next week on the topic of 'binomial nomenclature' or scientific names to explain how they work, where they come from and what they are for, look forward to it next Tuesday.

Geoff